Family Hellmann

Author: Manfred Brösamle-Lambrecht

A meagre existence as a small trader

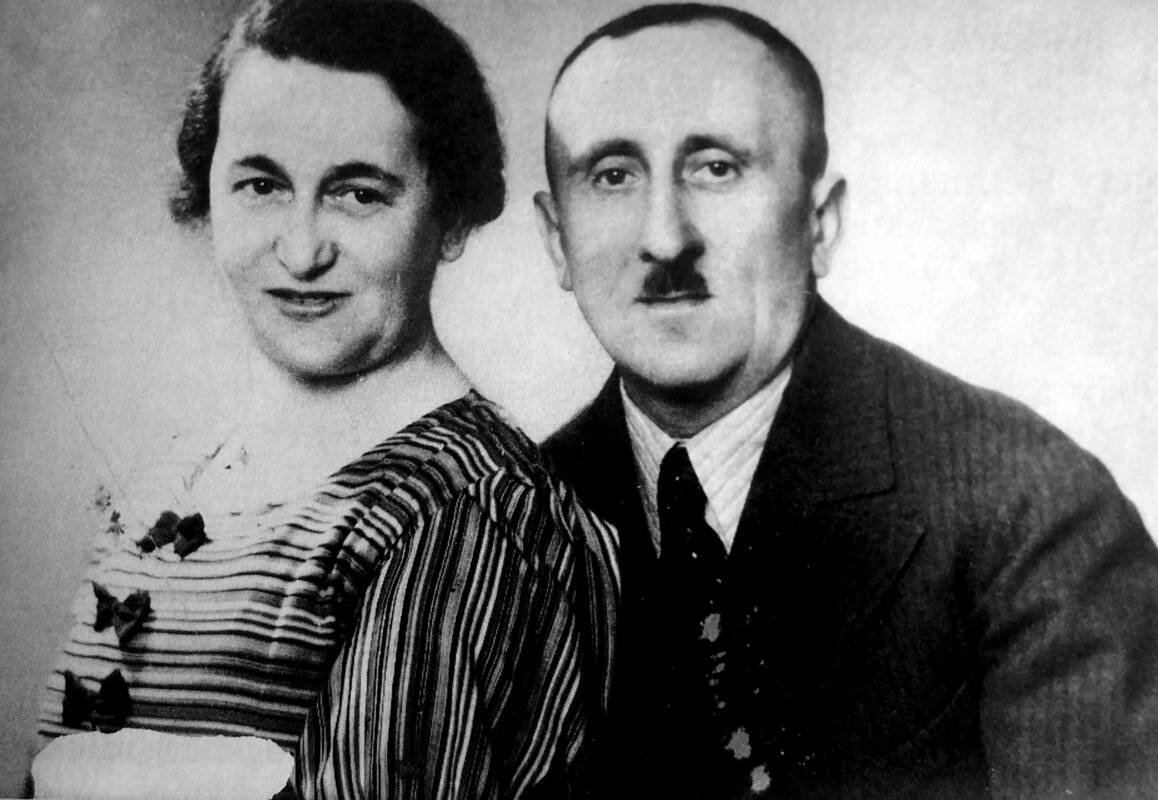

Max Hellmann was born in Altenkunstadt on 24 November 1889 as the son of the small trader Sigmund Hellmann and his wife Philippine, née Freudenthal. His father supplied farmers and small businesses in the neighbourhood with lubricants (oils and greases) in detail. The non-Jewish population called him pejoratively "der Schmierjud" (the lubricating Jew). Max Hellmann was drafted at the beginning of 1916 and deployed as an infantryman in France. He took part in several battles and was seriously wounded on June 15, 1917. In 1919, Max married Katinka, née Erlanger (*8 March 1893), from Fischach near Augsburg. Their son Siegfried was born in 1920.

The family lived together with his brother's family in his parents' small house in Altenkunstadt. Max Hellmann took over his father's business - he was also nicknamed "Schmierjud". He travelled around the surrounding villages on a bicycle with a heavy front and rear load, selling lubricants to farmers and businesses.

Photo: His parents' house in Altenkunstadt (Judengasse 1)

From small retailer to shop owner

At the beginning of the 1920s, luck was in Max Hellmann's favour: an eighth ticket in the lottery brought him a prize of around 10,000 marks and he was finally able to open the shop he had longed for. He bought the property at Bamberger Straße 25 in Lichtenfels, probably in 1924, moved to the district town with his family and set up a specialised shop for lubricants.

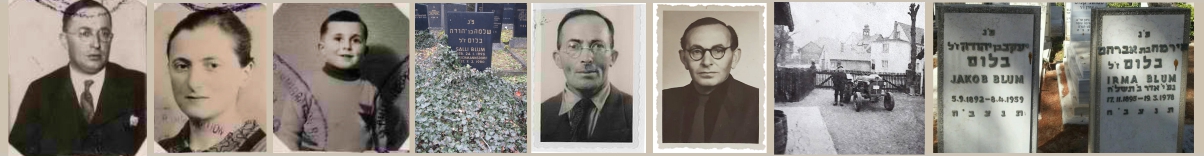

Photo: Hellmann's shop was located in the grey slated house on the far right

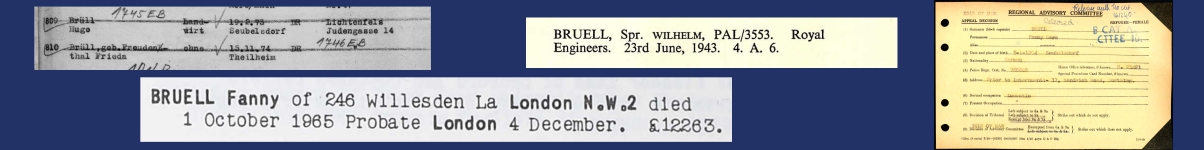

1938 ff.: Disenfranchisement and marginalisation

Max Hellmann's shop was looted and vandalised in the early morning of 10 November 1938. He himself was taken into "protective custody" for weeks. Expropriation and coercive measures by the regime subsequently led to the closure of the business and the sale of the property. In 1940, Max Hellmann and his wife were crammed together with the other Jews of Lichtenfels in the dilapidated "Jews' house" at Judengasse 14. Further harassment such as curfews, travel bans and the obligation to hand in winter clothing made life even worse.

We do not know how Max Hellmann earned his living. It is known that other Jews had to do forced labour in local businesses or on farms. A contemporary witness reports that he saw Katinka go to work every morning. She always tried to cover up the yellow Jewish star on her dark blue coat.

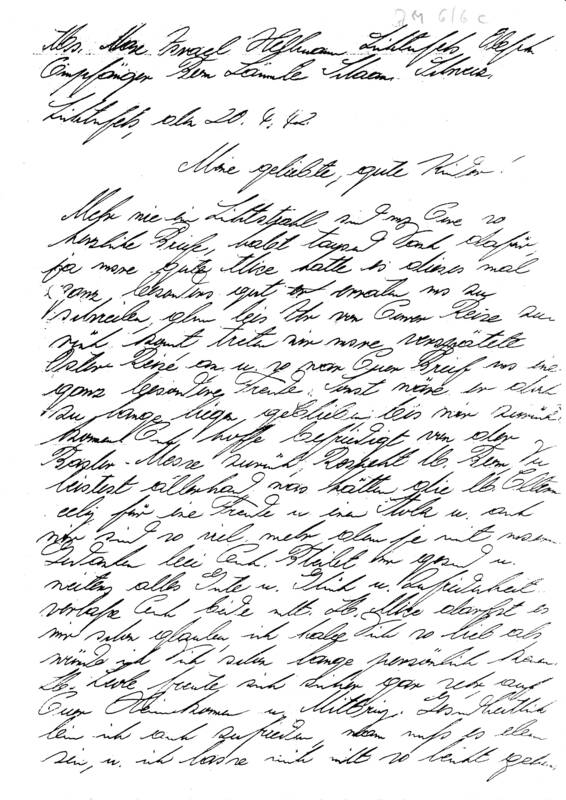

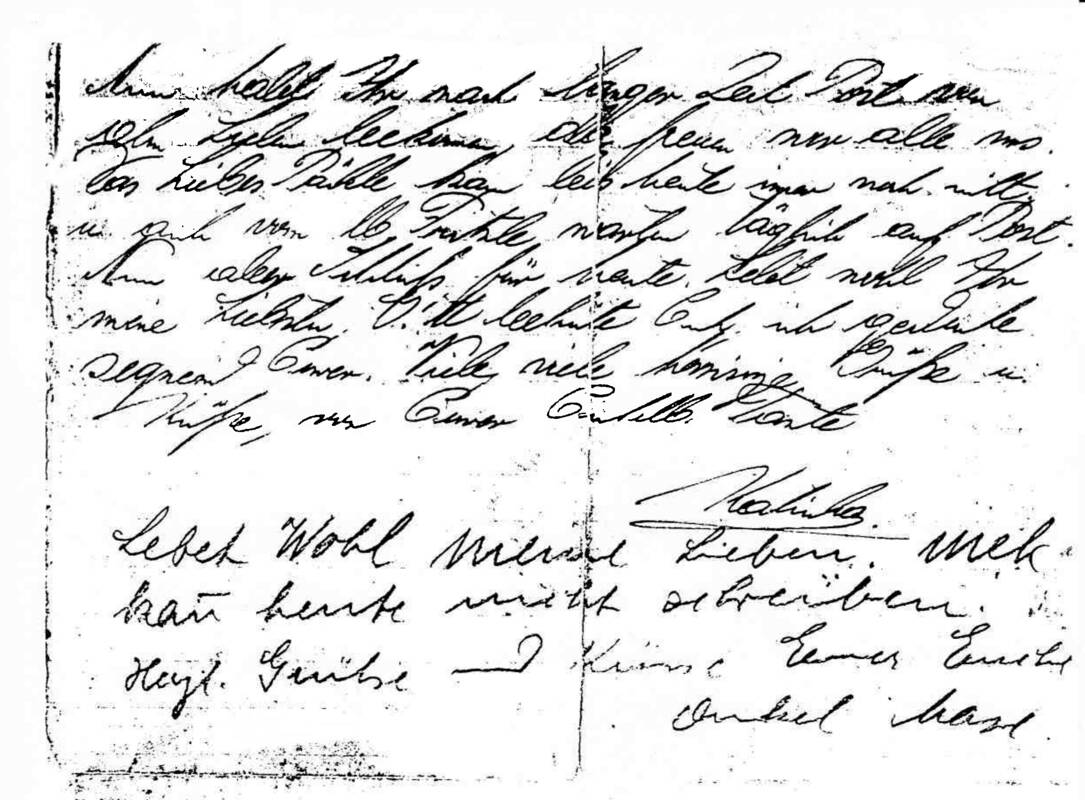

Last farewell letter five days before deportation

Five days before their deportation, Max and Katinka wrote one last letter to relatives in Switzerland. Such mail was rigorously censored, negative things were not allowed to be written. Between the lines, however, it documents the Hellmanns' desperate situation:

My beloved good children!

Your heartfelt letters are more like a ray of light to us, thank you a thousand times over for them, indeed our good Alice had guessed particularly well this time to write to us, because until you return from your journey we are starting our delayed Easter journey [she means the deportation] and so your letter was a very special joy to us. Otherwise it would have been left too long until we return. [...]

As far as my health is concerned, I am also satisfied, you have to be, and I do not let myself go so easily. Now you have received mail from your loved ones after a long time, we are all delighted. Unfortunately, the dear little parcel still hasn't arrived today and we're still waiting from dear Fritzle [the son]. Fritzle [the son] is waiting for mail every day.

But that's all for today. Farewell my dears, God keep you, I remember you with blessings. Many many greetings and kisses from your Aunt Katinka

Farewell my dears. I cannot write more today. Sincerely. Greetings and kisses from your loving Uncle Max

Deportation and murder

On 24 April 1942, Max and Katinka Hellmann marched to the train station at dawn together with four other Jewish citizens from Lichtenfels. In Bamberg, 103 Jews from Upper Franconia were loaded onto the DA 49 deportation train from Würzburg. The transport reached the south-eastern Polish town of Krasnystaw at 8.45 a.m. on 28 April; the 955 deportees had to march on foot to Kraśniczyn, 17 kilometres away. The ghetto there had been cleared two weeks beforehand by transferring the Jewish population to the death camps.

Max and Katinka Hellmann's subsequent journey cannot be reconstructed with absolute certainty. It is undisputed that they were murdered in one of the Sobibór or Belzec extermination camps over the next few weeks, as were all the occupants of the train. One source assumes that the Franconian Jews probably died in Sobibór on 6 June 1942.

The fate of the son Siegfried

It is a little known fact that the Jewish Mossad, partly in collusion with the SS, even Heydrich himself organised refugee ships across the Danube and the Black Sea to Haifa, which saved the lives of thousands of people threatened with deportation and murder. Siegfried also reached Palestine under adventurous circumstances and survived. His son Gavriel Hellmann now lives in Tel Aviv. The owner of the cleaning shop at Unteres Tor, Helene Sievers, reported in a letter to Max Hellmann's son in 1946 that Katinka Hellmann often visited her secretly during her lunch break to talk. What worried her most was the fate of her son, which was unknown to her. Max and Katinka probably never learnt that their son had managed to save himself.