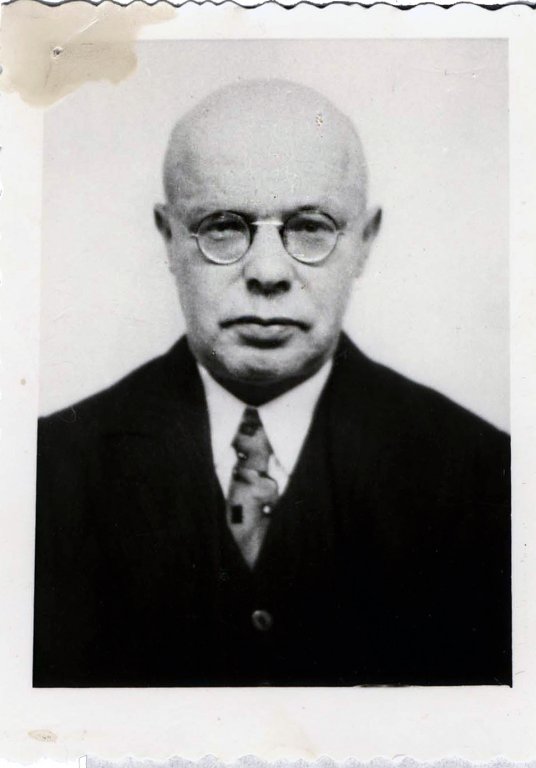

Arnold Seliger

Author: Manfred Brösamle-Lambrecht

Arnold Aharon Seliger was the fourth of seven children of the Jewish cattle dealer and merchant Maier [or: Meir] Seliger and his wife Klara, née Strauss. He was born on August 18, 1877 in Bad Orb (Hesse). Like three other of his siblings (Sigmund, Leo and Erna) he became a victim of the Holocaust.

Career as a Jewish teacher

Arnold Seliger underwent training as a Jewish teacher and cantor (preparatory training, followed by teacher training seminar) and found what was probably his first permanent position at the age of thirty in the Jewish community in Neustadtgödens in East Frisia. Now he was able to start a family and married Sofie Gutmann from Creglingen on July 8, 1908. On July 7, 1913, the couple's only child was born: their son Magnus Meir.

During the World War, Arnold Seliger served in the 78th Infantry Regiment.

As in all smaller towns in Germany, the Jewish community of the small East Frisian village dwindled after the First World War. Many Jews moved to larger centers or emigrated. In 1922, for example, the Jewish school in Neustadtgödens had to be closed, and Arnold lost his job. In 1924 he worked in Weener in East Frisia as a teacher, cantor and preacher. From there the family moved to Lichtenfels in 1925, where Arnold Seliger was employed as a teacher (and probably also as a preacher and shepherd) of the Jewish community in Lichtenfels. His duties also included religious education for the few Jewish students at the private Realschule Lichtenfels as well as for other children of the Jewish Diaspora in the rabbinate (e.g. in Kronach).

Life in the NS dictatorship

The Seliger family lived on the ground floor of the community-owned "Schächterhaus" Judengasse 14 next to the synagogue. Arnold and Sofie did not intend to stay in Lichtenfels permanently: in 1933/34 they had a house with several apartments built in Bamberg, one of which they planned to move into at the end of 1938; after the November pogroms, however, Arnold had to sell it again.

© Stadt Lichtenfels

© Stadt LichtenfelsThe son Magnus Meir no longer saw his future in Germany; he left the parental home already in 1933 after school at the age of twenty, moved to Bamberg, later to Strasbourg, and pursued his emigration to Palestine, which he also succeeded in: Despite great initial difficulties, he soon settled in Ramat Gan and took on Palestinian citizenship.

The November pogroms in 1938

The November pogroms destroyed the lives of Sofie and Arnold Seliger. What exactly happened on November 10, 1938, cannot be proven to this day. What is known for sure is that the synagogue was desecrated and looted by a jeering horde of Nazi thugs. Then they attacked the Seligers' apartment. Arnold Seliger was taken into "protective custody," and his wife was left unprotected at the mercy of the uninhibited perpetrators. The entire furnishings of the apartment were thrown into the street and destroyed, Sofie Seliger was maltreated with knives. Later she disappeared, only on December 3 her body was found in an arm of the Main near Reundorf. The Nazi authorities spoke of suicide. A post-war charge of murder and rape against known Nazi thugs was dropped for lack of evidence.

Walter S.G. Kohn watched parts of the events from the second floor of the Schächterhaus:

"Meanwhile, they set about the community center itself and broke the shutters of the apartment of teacher Seliger on the ground floor. He came up to us in his shirt. His wife stayed downstairs and was there when they destroyed everything that could only be hooked and torn small. Books, dishes, bedspreads were in tatters and shards, either in the apartment itself or in the street. Seliger [...] went out into the street after daybreak and was arrested for a short time. His wife was terribly affected by the loss of all her possessions, especially since her husband did not come back either.

From my own memory I do not know what happened to her. She was sitting under her debris when we left in the evening, then disappeared without a trace for weeks until her body was pulled out of the water near Reundorf. The Nazis said it was suicide; I only know that a few weeks earlier, in a conversation with my mother, she had taken the very strong stand that under no circumstances should one take one's own life, no matter how bleak and hopeless the situation might seem [...]"

Walter S.G. Kohn, Eyewitness

For Arnold Seliger the world collapsed. His abysmal despair speaks from a letter he sent to his son in Palestine ten days later:

"Lichtenfels, December 13, 1938.

My dear Magnus!

I received your letter of December 4. My grief over the loss of our beloved mother is still boundless, and I sometimes think I could no longer bear life. Everything has turned out this way, and unfortunately I cannot describe anything in detail to you. You know that we live next to the synagogue. I don't know if I can keep it up. I eat lunch and dinner at Mrs. Kohn's. For the rest, we have lost a lot. I have to stay in my apartment and own 2 repaired cupboards, the bookcase without glass, 1 sofa, 4 chairs and 1 bed. The dear mother took such pleasure in the beautiful things. The Jewish families here have to restrict themselves very much and often live together. You, dear Magnus, must pull out all the stops to be able to request me. I will not be a burden to you, but will try to be active. My bronchial catarrh is causing me discomfort, but I think that the warm climate in Erez cannot harm me. I only have a few books, which are not related to each other, and some clothes and linen. I have to pay a lot of taxes from my money. I will not have much left. But I can disregard everything, except the death of my beloved Sofie, which I cannot and cannot do. We had made such beautiful plans and were going to move to Bamberg on December 1; now I had to sell the field for a small price and I have to sell the beautiful house as well. It was a magnificent house. Man thinks, God direct s[…]

I rely on you completely; you are my only support now that my dear mother is no longer here. She had been missing for several weeks; on December 3 she was found dead and buried on December 4. What must I do now, if you have requested me? Find out so that you can advise your old father. I must pull myself together so that I do not lose my mind, so much has the death of my dear mother affected me. How are you in the meantime? I would be content with a dry piece of bread in Erez, and you know that I make no demands on life. My financial circumstances are also quite confused by this affair, but I can only tell you this verbally. I am at least comforted that you want to take care of me. My brothers and sisters have refused, since they have a lot to do with themselves, and Sister Lina died in the fall of 1937. […]

Farewell, greet Schulamith warmly from me and be also warmly greeted and kissed by your unhappy and deeply bent father Arnold.

NB. Today I was in Bamberg. I can only inform you that I must gather all my nerves in order not to go under completely."

Source: Lower Saxony State Archives Hanno-ver Nds.110 W Acc 31/99 No. 221729, re-gifting Magnus Seliger to Arnold Seliger.

Alongside the grief over the loss of his beloved wife came very concrete existential fears that would never leave him.

On August 13, 1939, he wrote to his son:

"[...] Next thing you know, compulsory labor service will be introduced among fellow believers. [Side note: If I do not do the service, I may lose my pension]. It could be that I would be drafted as a teacher for a large Jewish class, but I can no longer do the service because of my bronchial catarrh, and then I collapse, since I cannot talk for half an hour without interruption and would then have to spit blood.

Dear Magnus. What is to become of me? Physically no longer healthy, mentally no longer up to the mark, a plaything of strange people who do not mean well with me. My fortune is going, and I am not the master of it. I am awfully afraid of the future. [...]”

The family abandoned him. An emigration to Palestine to join his son failed despite many efforts. In Lichtenfels, with the end of Jewish community life, he no longer had a livelihood; he had to keep his head above water from savings and a pension. Like many other Jews, he believed that he could better escape the daily reprisals of the system in the anonymity of a large city; however, his plans to move to Munich fell through because of the high cost of living there.

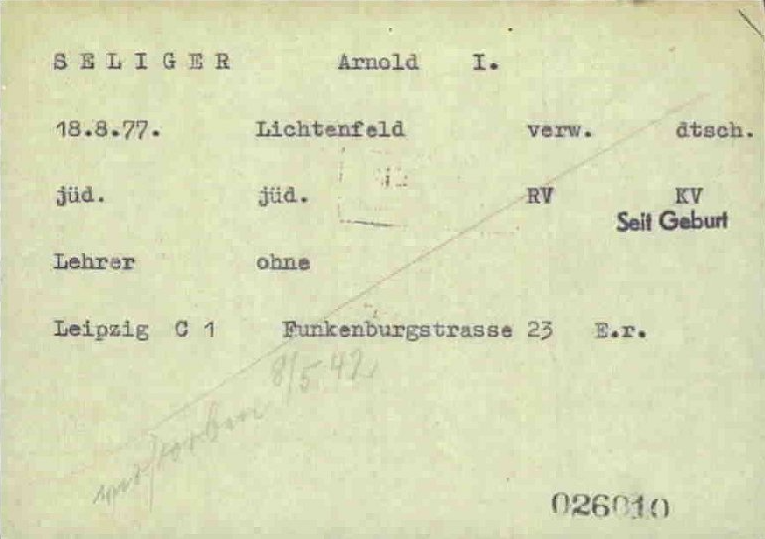

Last years in Leipzig

So in 1939 he moved to Leipzig, to Funkenburgstraße 25, to a boarding house in a first-floor apartment, but he did not feel comfortable there because of his bronchial catarrh, so in 1940 he moved to the house next door to another boarding house landlady.

Leipzig's Waldstraßenviertel was a Jewish residential area, and we know from another source that the Chaim Rodoff family of ten lived in the same house; seven members of this family (father, mother and the five youngest children) were deported to Riga in January 1942. They were all murdered in the Shoah.

Arnold Seliger moved once again to Humboldtstraße; shortly before his already scheduled deportation, he died on May 8, 1942, in the General Jewish Hospital in Leipzig. The causes of death were given as heart muscle degeneration and lung disease.

Quellen: Deinlein, Vera, https://www.bllv.de/projekte/geschichte-bewahren/erinnerungsarbeit/lehrerbiografien/arnold-seliger/

and own research.